“Re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, and dismiss whatever insults your own soul. If done, your very flesh shall be a great poem, and have the richest fluency, not only in its words, but in every motion and joint of your body.” Walt Whitman

I’m not sure if I specifically knew the quote above by Walt Whitman when I set out on my journey to Vermont. But I do know that in addition to simplifying and listening to my life, I also had a strong inner intention, spoken or simply felt, to reexamine and hopefully peel away from the teachings that I believed had done such harm to my mind and body.

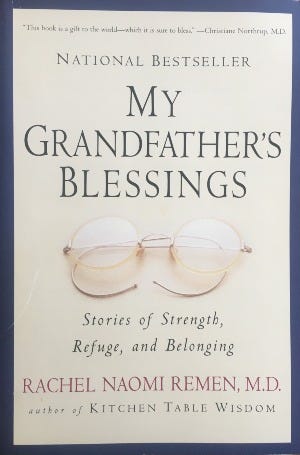

I was bolstered by the quote of Rachel Naomi Remen in her book My Grandfather’s Blessings, “Recovering a greater compassion may require us to confront the core values of our culture.” I’d discovered this book on the shelf of the guy I’d been seeing the year before I left for Burlington. Similar to Parker Palmer, Remen writes a lot about the wholeness that exists innately within human beings even as our larger society and institutions may focus more on our brokenness and pathologies.

As a medical doctor with years of experience working with patients with life threatening and chronic conditions, she caught my attention with her integrative and holistic approach to medicine and health care rather than a one-sided reliance on allopathic or conventional western medicine.

When I was first diagnosed with type I diabetes, in addition to prescribing insulin, my doctor recommended that I should begin taking a statin for high cholesterol, an antihypertensive for high blood pressure, and continue taking a low dose antidepressant for my anxiety and depression. But before going on these additional pharmaceuticals, I wanted to see if taking steps to “come out” would unleash some pent up motivation and joy for life, thereby naturally improving my health and well-being. This seemed quite plausible to me.

So in addition to the teachings of orthodox Christianity and socially conservative culture, my reexaminations would now include mainstream medicine. Hell, I would reexamine any traditional authority that seemed to encroach on my autonomy and well-being. This edgier and more defiant side of my personality was still new and emerging for me, although it had certainly seethed out of me at times back in Mississippi — a mix of frustration, anger, and simple boredom with the same ole stances and perspectives.

I had a friend and colleague back in Mississippi tell me, “It sure would be nice to know what you really think and feel about things.” And I remembered a previous church member in Alabama shared that I often seemed like a politician or diplomat, never wanting to offend anyone — always trying to say and do the right thing. Perhaps this is a strain many first born children can feel to be obedient to authority and agreeable with others, but I now felt constricted by this role. As a child and youth, I’d enjoyed acting and playing certain parts on stage, following the scripts, performing the lines and actions of other characters, safe within a spotlight of anonymity. But now I found acting a certain way exhausting. I felt typecast as the responsible and compassionate one — trying to appear mature, wise, or well-adjusted all the time. Vermont was a canvas for me to throw out the script, go off beat, and get a little messy.

As I sat in the silence of a number of Quaker meetings waiting for that “still small voice”1 within me to emerge, I was a bit surprised when I felt compelled to stand and speak the words, “Our society seems to prefer our people like we prefer our food — wrapped in plastic.”

Was this the voice of “God” speaking through me? I doubt it. Was it a broad generalization about our society? Somewhat. Was it peculiar, unorthodox, even inappropriate within the tradition of Quaker worship? Perhaps, although no one made me feel that way. What was it then? It was a sincere statement, however hyperbolic, of what I thought and felt of the pressures to conform, even to be concealed by the expectations of family, a church, a particular culture, or a broader society. But I wasn’t concealed on this day. And it felt freeing to remove a bit of the metaphorical synthetic polymer from my mouth in order to speak. And instead of being silenced, shamed, or shunned, I would soon be embraced by this group of caring Quakers.

Question - Have you ever taken time to reexamine what you've been taught or told to believe, to discern what you truly think and feel? More importantly, have you dismissed what insults your own soul, reason, and experience? How did that feel?"

*Thanks for reading and/or listening. Please join me for more next week. To read from the beginning go to Why I'm Writing.

Have thoughts, questions, or feedback? Please comment — it means a lot to hear from you on this mostly solitary and introspective writing journey that I’m on.

“Unprogrammed” Quaker worship is more like sitting in silence with other people and listening for “that still small voice,” whether one attributes that to “God” or to one’s inner voice or truth.